Stereotypes are often created in order to demean certain groups of people. There is usually a kernel of truth behind them, to be sure, but in serving their more sinister purpose most stereotypes blow that kernel out of proportion and/or unjustly link it to other unsavory characteristics. Eventually, though, some stereotypes become little more than a harmless joke.

Take the Irish and potatoes. Even before potato famine of the 1840s, the widespread reliance of Irish tenant farmers on potatoes became the source of a handful of derogatory nicknames and slang among the English. (Even the word Irish itself was used as a mocking adjective.) Worse nicknames welcomed the more than four million Irish refugees who migrated to America before, during, and after the potato famine, including several based on potatoes. These stereotypes were far from harmless. Violence and political repression faced Irish Catholics on both sides of the Atlantic, and they were often considered a different race of people altogether. (Unfortunately, little has changed. We still see almost rabid hatred applied not to those who abuse power and wealth, but rather to those who are poor and seeking refuge.) Stereotypes were a way of not-so-subtly reminding everyone about the existing power dynamic—the Irish were second-class citizens. Behind the name-calling was an implicit threat of something worse.

But as we’ve seen repeatedly among oppressed groups of people, the Irish found solidarity in the very things that made them stand out. They took pride in eating potatoes and in re-creating a sense of community at the local pub. Eventually—it took at least a century—descendants of Irish immigrants integrated into broader American society and no longer bore the brunt of nativist sentiment. Light skin certainly helped. (Some Americans, including many Irish immigrants and of some of their descendants, found other groups to fear and to hate.) Still, despite all the pressure to assimilate completely, certain aspects of the Irish cultural legacy lived on, including a diet rich in potatoes.

In the Irish part of my family, the potato stereotype held fast and true. If anything, it grew stronger in America. My mother has fond memories of her grandparents Basil and Isabelle (Daly) Jordan. They were both American-born, but they retained important aspects of their Irish heritage. According to my mother, Basil loved potatoes. “No meal is complete without a potato,” he always said. And he meant it. He might have a fried potato for breakfast, boiled potatoes with his lunch, and meat and potatoes for dinner. He once told my mom she looked too thin (she has never had this problem) and should eat more potatoes.

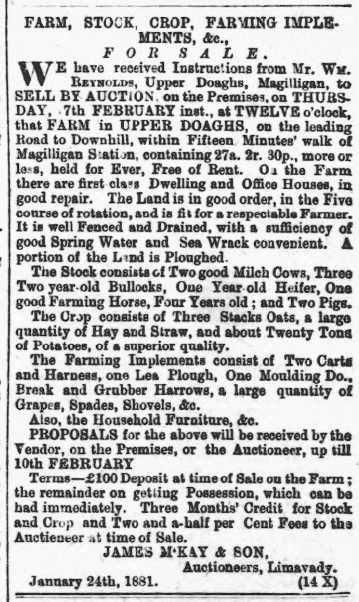

Isabelle’s family, too, had deep, tuberous roots in Ireland. In fact, what prompted me to write this post was a recent discovery about Isabelle’s maternal grandparents, William and Mary (Cramsie) Reynolds. I was working on an article about the Reynolds family for an upcoming issue of The Septs, the quarterly publication of the Irish Genealogical Society International, when I came across a sale notice for the Reynolds’ farm in The Derry Journal. It was January 1881, and the family was preparing to leave County Derry for America that spring. With only a trunk or two to carry their most necessary and valuable possessions, William and Mary had to sell not just the farm land but almost everything on the farm too: livestock, stored crops, farm implements, household furniture, and more. They ran a modest farm and, as Catholics, were in fact fortunate to own the land they cultivated. Among their modest possessions, one thing caught my eye. According to the sale notice, “The Crop consists of Three Stacks Oats, a large quantity of Hay and Straw, and about Twenty Tons of Potatoes, of a superior quality.” It was true! Here was proof that some of my Irish ancestors grew—and apparently subsisted on—tons and tons of potatoes and little else, even thirty-five years after the Great Hunger. Twenty tons of potatoes was more than enough to carry the family of two adults and five children through winter with some to spare.

A final point. It’s worth remembering that many of the foods we identify with certain ethnic groups reflect not just voluntary cultural choices, but choices imposed by poverty. Irish peasants ate mostly potatoes and milk because they could afford little else. When we ask, “why did the Irish eat so many potatoes?” our answers are partly to be found in English colonization and the confiscation of land by Protestants. Held in poverty, most Irish Catholics could afford nothing but the potatoes they grew on their small plots of rented land. William Reynolds’ parents Frederick James Reynolds and Mary Hasson were apparently quite poor. They had emigrated separately to America in 1848, arriving in Philadelphia with little more than the clothes on their backs. (Philadelphia was not a welcoming place for Irish immigrants in the 1840s. When and why Frederick and Mary Hasson Reynolds returned to Ireland and how they acquired land there are some of the questions raised in my article.)

Like the Irish and potatoes, African-American “soul food” reflects a history of oppression. “Soul food” developed from slave cooking in the American South and, after the Civil War, in rural and urban poverty throughout the U.S. While we take pride in all the creative ways the Irish found to cook potatoes and the genius of African-Americans to create “soul food” from scraps, we must remember that if given the choice most of these people would have preferred the varied diets, unusual flavors, and luxuries (like sugar, tea, coffee, and better cuts of meat) that were eaten by the upper classes.

When we think about our cultural inheritance from ancestors in such groups, we ought both to celebrate the perseverance and resourcefulness embodied by their cuisine and recognize the systems of power that limited their culinary (and nutritional) choices in the first place. It’s OK to be both proud and upset by the truth of your family history. So have a laugh when you find proof that the kernel of a now-harmless stereotype turns out to be true, but remember that such stereotypes usually have deeper, more sinister histories. Consider this fact not just when researching your own family’s immigrant ancestors but also when you look at your neighbors today.