Our next victim in the “You Died How?” series is Burgess Nelson. He was my 6x-great-grandfather. The story of his life can be seen as a parable of religious life in the early years of the American Republic. The story of his death has a lot to teach us about the importance of a family’s legacy and about the reliability of certain kinds of genealogical records.

Let’s start with a quick summary of Burgess Nelson’s life, as many of his descendants first encounter it. The following excerpt comes from the 1882 History of Mercer and Henderson Counties [Illinois], one of those massive county histories written in seemingly every county in the country during the late 19th century. The book includes a short sketch of George Cronkite Nelson, Burgess Nelson’s grandson through his son Elisha. It reads, in part:

Burgess R. Nelson, father of Elisha Nelson, lived in Maryland all his life. He was a minister of the Methodist Episcopal faith. He was a successful financier; a proprietor and director in a bank corporation. He lived to the extreme age of ninety-eight years, and then was murdered for his money [emphasis added]. He was a man that was highly respected for his good qualities and high integrity. He frequently visited his son, Elisha, in Ohio, making the entire distance to and from on horseback. He served in the Revolutionary War.

Some of these details turn out to be true. As we shall see, Burgess was a minister and he was involved at least peripherally in banking. Some of the other “facts” were a complete fabrication. There is no evidence, for example, that Burgess Nelson served during the Revolution. Most importantly for us, he was not murdered. In the rest of this post, we’ll take a closer look at Burgess’s life as well as his death. As it turns out, the truth of his death might be stranger than the fiction.

“The Reverend gentleman”

From the moment of Burgess Nelson’s birth, his life embodied the national religious rejuvenation that scholars call the Second Great Awakening. According to his gravestone, he was born January 1, 1764, probably in modern Carroll County, Maryland (which was then part of Frederick County). As it happened, Frederick County was also the birthplace of American Methodism. A few years before Burgess was born there, an itinerant preacher named Robert Strawbridge had come to the county from Northern Ireland and begun to attract converts. The first sermons took place in his little log cabin home in Sam’s Creek, Maryland, but he was soon a well-known preacher throughout the mid-Atlantic. Strawbridge set up the first Methodist societies in Delaware, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

Perhaps Burgess’s parents were among Strawbridge’s early converts (though who exactly his parents were is uncertain). Perhaps Burgess himself became a convert after hearing a sermon by Francis Asbury, who arrived in the Mid-Atlantic from England in 1771 as an official delegate of John Wesley. Whatever the case, Burgess grew up near the heart of the growing Methodist movement. He came of age alongside the religion. He was 20 years old when the Methodist Episcopal Church was formally founded at a conference in Baltimore in December 1784, with Asbury at its head.

However he was introduced to Methodism, Burgess was obviously quite taken by the promises of the faith. He was ordained a Methodist minister—definitely by 1801 but probably long before that—and he remained active in the church for the rest of his life.

Methodism appealed to many Americans because of its focus on the faith experience of each individual. Whatever one’s station in life, God offered hope of salvation. As American political democracy gradually expanded during the early 19th century, so too did faiths like Methodism, which were underpinned by similar democratic ideals. Burgess Nelson believed in these things, and he spread the Word to anyone who would listen. He preached to rich and poor, white and black, free and enslaved, even to members of secret societies. In April 1824, for example, a Frederick County Freemason Lodge “voted the ‘Rev. Burgess Nelson a set of silver tea spoons with the letters B. N. engraved on the upper side in the usual place for initials, with the square and compasses under said initials and the name of the Lodge on the under side.’ . . . (The Rev. gentleman had officiated for the Lodge at the funeral of a visiting Brother; John Holmes, of Lodge No. 1*, Ohio.)” (source)

A few years before that incident, Nelson had preached a sermon at a church in Elk Ridge, Maryland, southwest of Baltimore. Listening intently in the audience that day was a 19-year-old slave named John Baptist Snowden, who remembered the sermon as a turning point in his religious development.

The Rev. Mr. Griffith made another appointment to preach in the same church in a few weeks, but failed to get there to fill the appointment, and the Rev. Burgess Nelson preached in his place. He took his text from the prophecy of Daniel 12:2: “And many of them that sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life and some to shame and everlasting contempt.”

The sermon was preached in the month of April, 1820. The earnest words of the preacher as they came, prompted by a loving heart, moulded (sic) by a keen intellect, warmed by the fire of Jesus’ love, and a consciousness of their great importance flowing in a continuous stream of sacred eloquence, sent conviction of sin and guilt to my heart. At the close of the service I returned home with a heavy heart and a troubled mind. But I managed to conceal my convictions and moved around as if nothing was wrong. In the evening I fed the cattle and did my other work as if all was well with my soul. I appeared calm without, but there was a mighty raging of the troubled waters in my poor sin-smitten soul.

After dark I went some distance from the house, knelt down and prayed as best I could. This done, I felt somewhat relieved and returned to the house still troubled. Monday morning I arose and went about my work as usual, but with very different feelings. I was sent to the woods to cut wood. After cutting down one tree, the burden of sin was so heavy that I put down my axe and said, “If my owner come or not, I was going to seek the Lord.” I went some two or three hundred yards from my work and fell on my knees and prayed earnestly to the Lord to pardon my sins and convert my soul. I had not prayed very long before God, for Christ’s sake, pardoned my sins and set my soul at liberty and put a new song in my mouth.

I cried, “Glory to God! Praise the Lord for what He has done for me.”

Snowden’s description of his conversion—an inspirational sermon followed by an ecstatic personal experience of God’s grace—was typical of the Second Great Awakening. (The famous camp meetings from this era were gatherings of individuals experiencing ecstatic moments in the presence of others.)

In April 1823, exactly three years after hearing Nelson’s sermon, Snowden, “the uneducated slave boy,” gave a trial sermon at the Methodist’s Quarterly Conference and earned a license to preach on behalf of the church. A few years after that, he bought his own freedom and became a Methodist circuit rider. Once free, he moved to Westminster in modern Carroll County. He met his wife there and called the city home for the rest of his life. We can only speculate that he chose to go to Westminster to be near Burgess Nelson, who lived nearby.

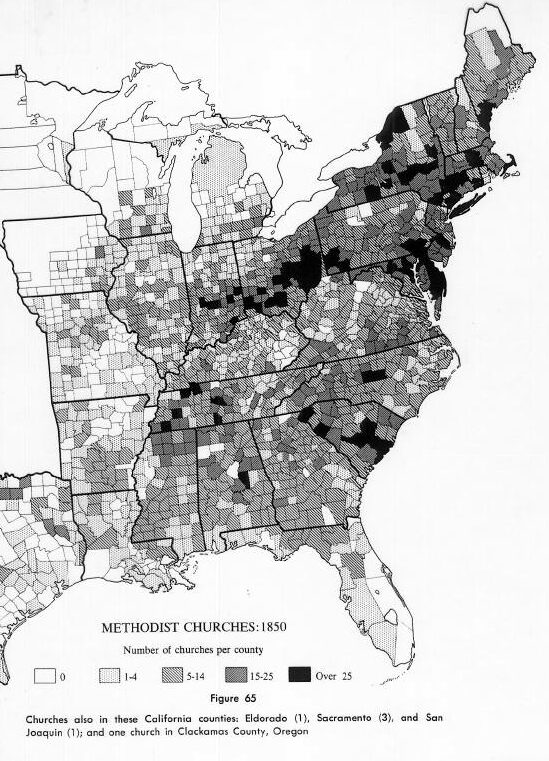

Snowden’s experience demonstrates the power preachers like Burgess Nelson had to change the shape of American religion in the early 19th century. Nelson and hundreds of other preachers, ministers, circuit riders, and laypeople of faith helped grow Methodism into the largest religious denomination in the United States by 1820.

A crisis of conscience

The first serious crisis for the Methodist Episcopal Church was the same crisis that later tore apart the whole nation: the question of slavery. Indeed, the division of the church into Northern and Southern branches, which took place in 1844, was viewed as a bad omen for the nation as a whole. The same crisis of conscience affected Burgess Nelson personally. He was a slave owner. In 1820, the same year he preached to Snowden, Nelson owned three slaves according to the U.S. census. Two free blacks also lived with the family.

American Methodists had struggled with the existence of slavery since the very beginning. During a 1780 conference in Baltimore, Francis Asbury demanded that Maryland preachers promise to free their slaves. He later sent anti-slavery petitions with circuit riders in Virginia. Ultimately, however, anti-slavery agitation by Asbury and other religious figures failed to change the minds of enough Southern legislators (many of whom were slave owners). Ratification in 1789 of the new U.S. Constitution, with its provisions for the continuation of the slave trade and extra voting power for slave owners, ended all practical debate on the matter. Slaves were property even if their souls could be saved.

By the 1830s, religious revivalism had stoked the spirits of Americans from upstate New York to backwoods Tennessee. In the North, widespread religious fervor was one of the driving forces behind the growing Abolitionist movement. More and more people were coming to believe that slavery went against the teachings of the Bible. It was morally wrong to hold another human soul in bondage, they believed, especially in the violent manner of the American South, where whippings, rape, and other forms of abuse were common. To degrade and dehumanize another person in this way was the exact opposite of raising him or her up to the grace of the Lord. To support their argument, abolitionists publicized stories told by slaves themselves.

Every slave had stories like John Baptist Snowden (though his were not published until decades after the Civil War). He could speak of his grandmother, “brought to this country by the men-stealers who tore her away from her native land.” He knew his father “was a good husband and kind father” even though he was enslaved on a plantation seven miles away from John and his mother. He “came to see her and the children several times each week, walking the seven miles after working hard all day.” But that meant that “We children did not see much of father during the week, as it was late before he got home at night, and had to leave long before it was time for us to get up in the morning.” Snowden passed into the possession of five different owners by the time he was 13 years old. He had to beg his third owner not to sell him to slave trader who would tear him away from his family and take him south.

In the South, the Bible played a central role in the public defense of slavery, which also emerged more vocally during the 1830s. Slavery was a positive good, argued people like South Carolinian John C. Calhoun, and the Bible said as much.

Maryland was, quite literally, in the middle of the conflict. It was a slave state, but one made up mostly of exhausted tobacco plantations. The real money was to be made on the cotton frontier south and west. The most direct consequence was that tens of thousands of Maryland slaves were sold south, their owners pocketing the cash. A more subtle consequence was that, since slavery’s economic value was diminishing in the East, it was easier for some slave owners in states like Maryland and Virginia to consider a time when the institution might end altogether. Some Maryland slave owners voluntarily emancipated their slaves.

In May 1836, the slavery issue which had lain dormant beneath Methodism for decades erupted at the General Conference in Cincinnati. When two abolitionist members lectured in the city during the Conference, a number of Conference officials formally censured them. Leading the anti-abolition charge was Marylander Stephen G. Roszel from the Baltimore Conference. Following his direction, the General Conference condemned the abolitionist speakers and supported an official decree (proposed by Roszel) to suppress “modern abolitionism” wherever such “agitation” occurred. The 1836 conflict set the stage for the denomination’s North-South division in 1844.

Once again, it’s uncanny how closely Burgess Nelson’s religious journey mirrored the national one. For Burgess, the issue was personal. It was a crisis of his own conscience. He encountered enslaved people on a regular basis as both an owner and a preacher. He understood them as spiritual beings, just as capable of salvation as their white masters. As the issue came to the fore nationally, the lines of argument sharpened on both sides—helping to frame the debate in his own mind. The obvious brutality of slavery was set against the psychological defenses of the institution that had been ingrained in white slave owners like him since birth. Moreover, Burgess knew as well as anyone that religious leaders like him were supposed to embody moral authority. But which side was in the right?

We’ll never know completely what went on inside his head. But we do know the outcome. On March 10, 1836 (just two months before the contentious General Conference in Cincinnati), now the owner of two slaves, Burgess Nelson signed a deed that legally established his plan to free them. His slave Elizabeth Ann, then about 15 years of age, he would free on April 1, 1840. His slave John, about nine years old, was “to be free on the 1st day of April, 1852.”

![Burgess Nelson deed to free his two slaves. Report of Manumissions, Frederick County, March 10, 1836, Henry Schley: Burgess Nelson will free Negro Elizabeth Ann in 1840 and John in 1852 [Frederick County]. Maryland Manuscripts collection, item 3124. http://digital.lib.umd.edu/image?pid=umd:89361](http://www.genealogicresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Burgess-Nelson-Report-of-Manumission-1836-Frederick-County-MD2-page-001-839x1024.jpg)

A legacy to protect

This brings us at last to Burgess Nelson’s death. Revisiting the 1882 description submitted by his grandson George C. Nelson for the local county history, we recall that Burgess was supposedly involved in banking and “was murdered for his money” at the “extreme age of ninety-eight years.”

Burgess was involved in banking, at least as an investor. In 1829, he was listed as a capital subscriber to the Farmers’ and Mechanics’ Bank of Frederick County. It’s possible he was a co-director to that bank’s predecessor. (More research is needed here…)

But Burgess was not murdered for his money. When George Nelson submitted his account to the editors of the county history, he covered up the truth of his grandfather’s death. Just like the fabrication of Burgess’s Revolutionary War service, George was embellishing his own pedigree and protecting his family’s legacy. The murder George invented allowed him to put the blame on someone else, when in truth Burgess Nelson killed himself.

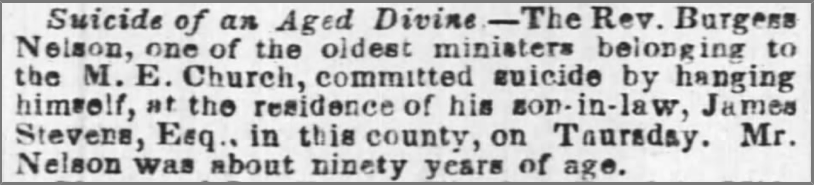

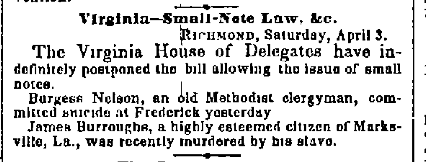

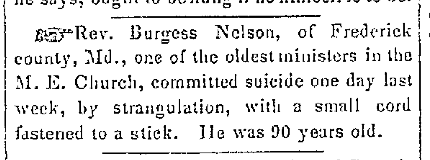

The report of his suicide was first published in the Catoctin Whig and/or the Frederick Citizen. The Baltimore Sun ran it a few days later and papers all over the country picked it up from there. The death of the “aged divine” was reported everywhere from New York City to New Orleans. Each report was slightly different (and sometimes contradictory in detail). None of the accounts says why he killed himself.

But look at the date. Burgess Nelson hanged himself on Thursday, April 1, 1852, the very same day he was supposed to emancipate his slave John. The timing is strongly suggestive of a connection.

One might propose, for example, that Burgess Nelson was a sad, lonely old man, who chose to live only long enough to see his last slave freed. (This won’t be the last time we encounter lonely old men committing suicide in the “You Died How?” series.)

Alternatively, freeing John may have caused the 88-year-old minister to confront once and for all the greatest moral dilemma of his life. In this final judgment, as it were, perhaps he fell into a bout of severe self-loathing and depression and killed himself out of guilt, shame, or fear of eternal damnation for having owned other human beings. Maybe he was ruminating on the prophesy in Daniel 12:2 that had caused John Baptist Snowden so much anxiety: “And many of them that sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life and some to shame and everlasting contempt.”

For now, all we have to go on are the 1836 manumission deed and these newspaper reports that give the same date for both events. The rest is pure speculation. We don’t even know if John was actually freed that day. For all we know he had died prematurely or been freed ahead of schedule.

The moral dilemma of slavery weighed heavily upon the consciences of our 19th-century forefathers, people like Burgess Nelson. It ought to weigh on our shoulders too. I hope to find out what became of Elizabeth Ann and John, the two slaves whose names we know. We have a duty, I believe, to help recover the family histories of slaves who once belonged to our ancestors. It was our ancestors, after all, who obliterated that history in the first place by stealing husbands from wives and children from parents for their own economic gain.

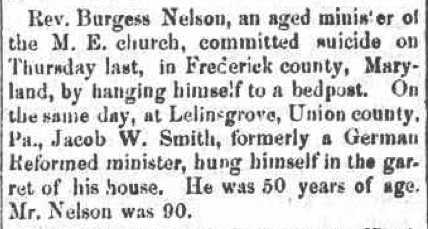

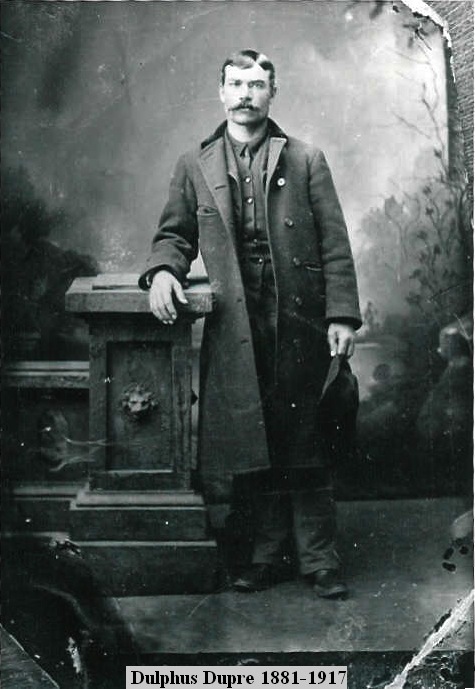

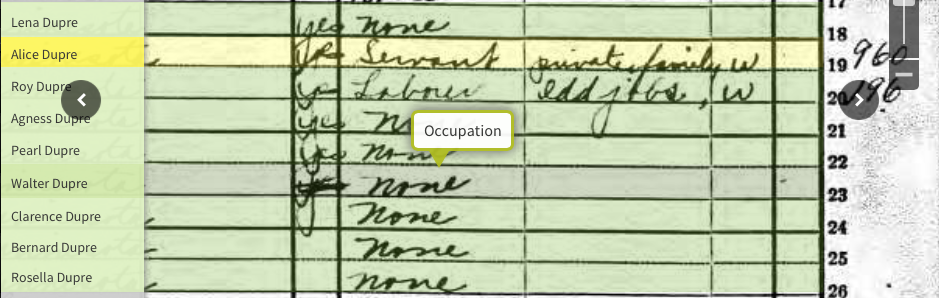

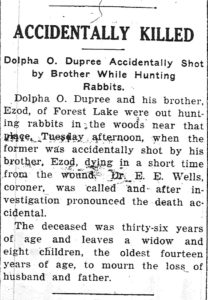

The first unfortunate soul in our exploration of unfortunate deaths is my great-great-grandfather Oliver Delphis Dupre.

The first unfortunate soul in our exploration of unfortunate deaths is my great-great-grandfather Oliver Delphis Dupre.

Welcome to a brand new series called “You Died How?”

Welcome to a brand new series called “You Died How?”