My grandmother Margaret died last month. Obituaries are expensive, so hers was kept fairly brief. I completely understand that decision, but I also think people deserve to be remembered in more complexity than two paragraphs can offer. So I decided to write Margaret’s Life Story. Aided by the collection of documents, photographs, and memories people shared at the funeral, I’ve been able to put together an extended narrative and photo essay that will, I hope, honor her legacy and help her descendants learn about her life and times long into the future.

I am posting this today because it would have been Margaret’s 96th birthday.

An Active Childhood

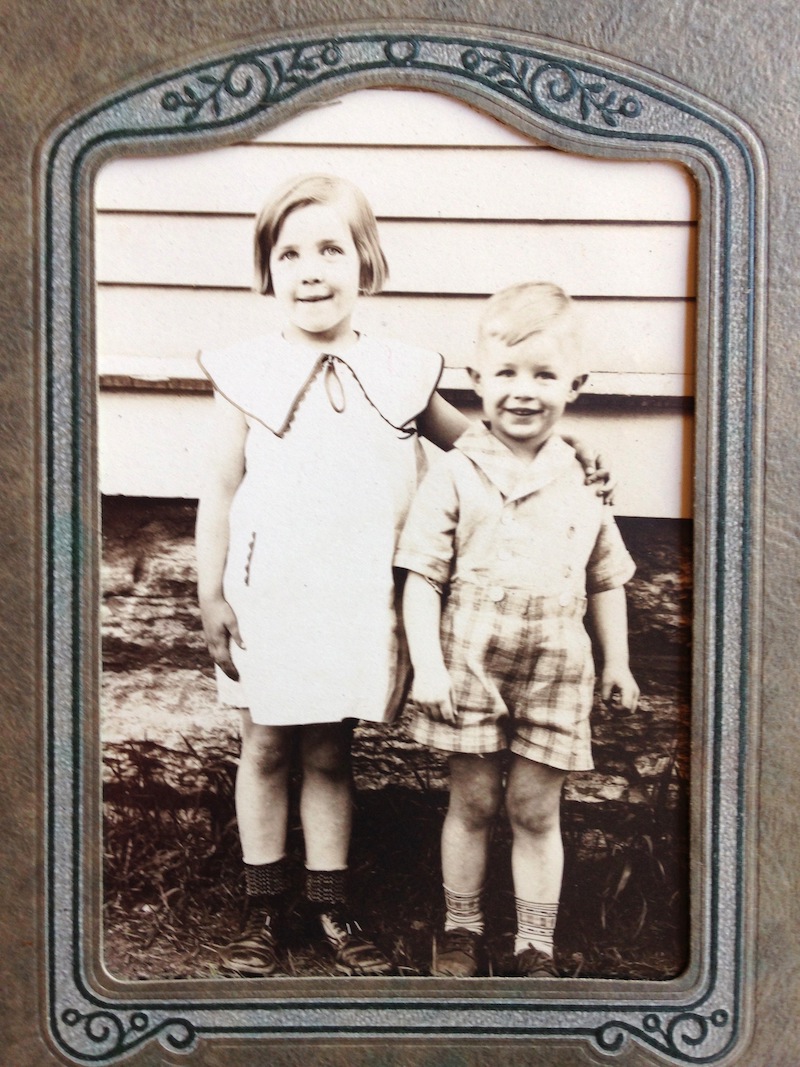

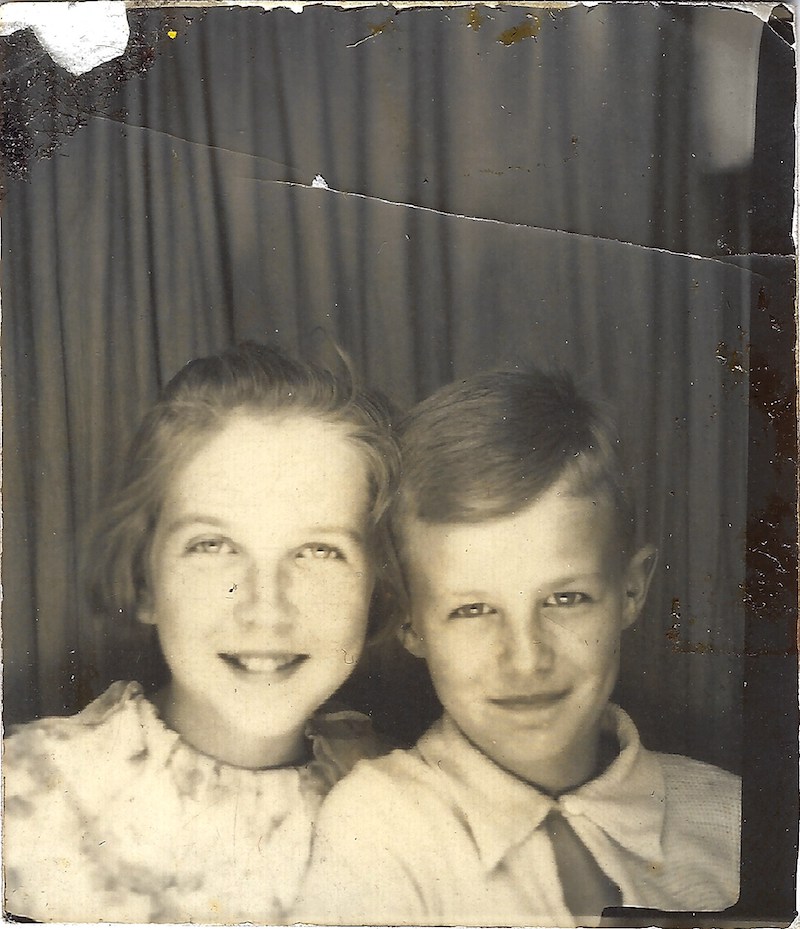

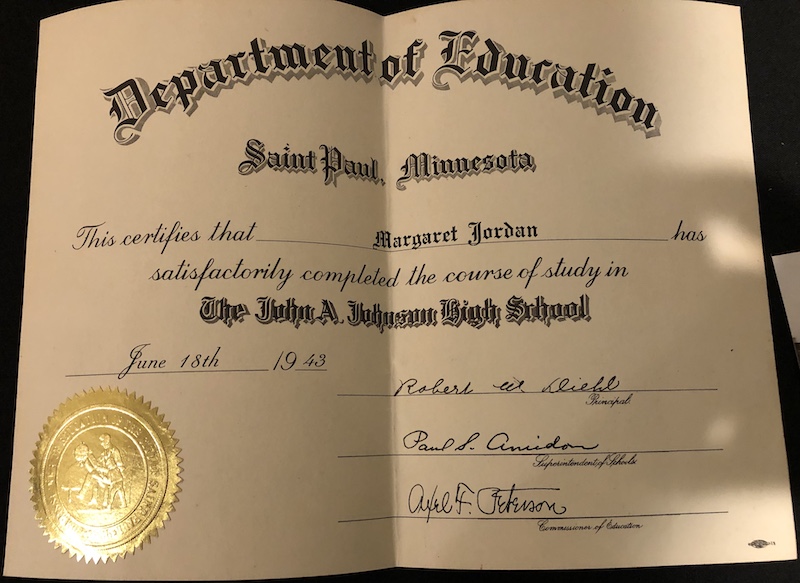

Margaret Anne Jordan was born April 17, 1925, in St. Paul, Minnesota. She was the eldest child of Basil and Isabelle (Daly) Jordan, who had married in St. Paul the previous July. Margaret grew up on the east side of St. Paul with her younger brother Patrick. She attended St. Patrick Catholic School through eighth grade and then Johnson High School.

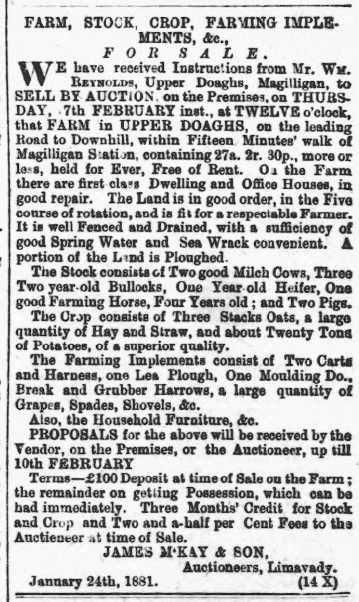

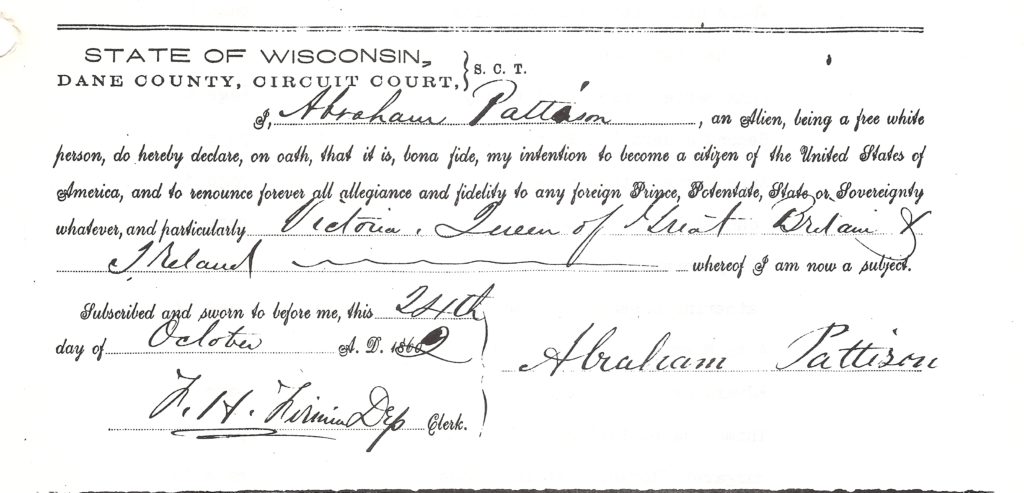

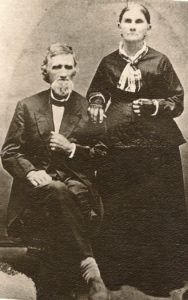

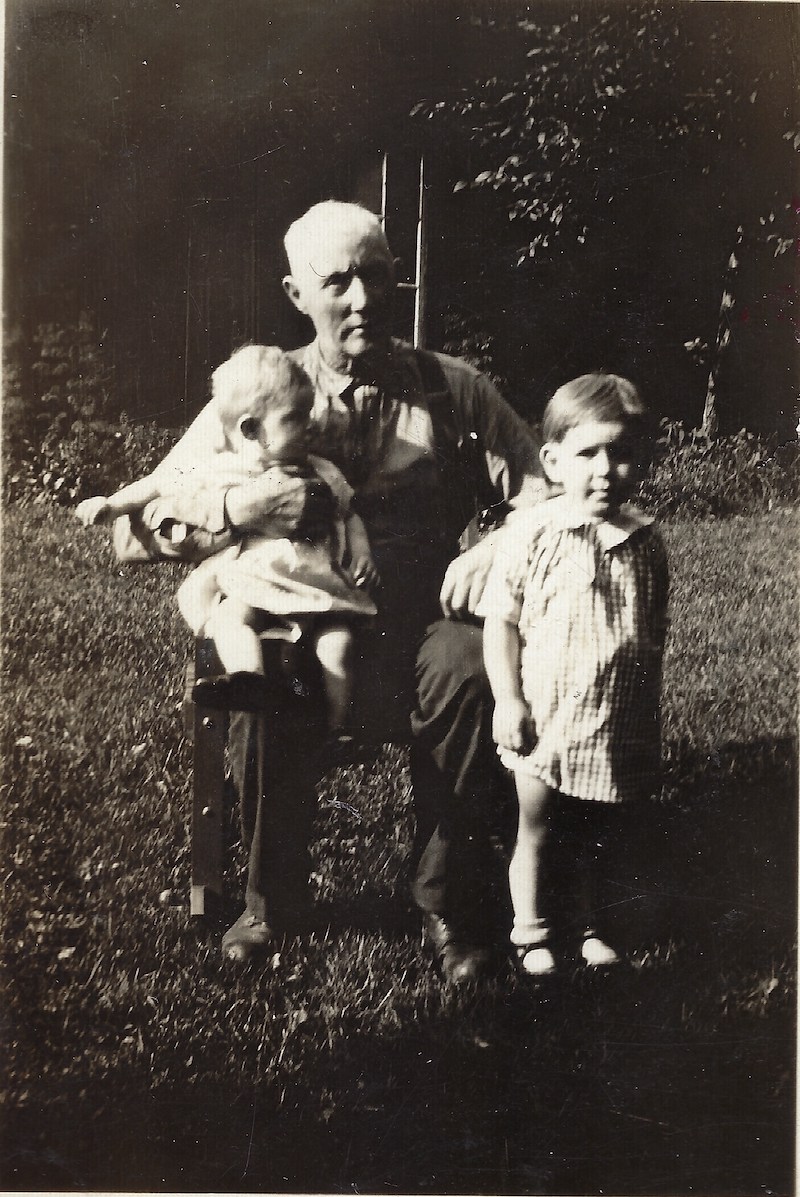

As a child, Margaret spent a lot of time with her maternal grandparents, Ed and Jane (Reynolds) Daly. In 1924, while Margaret was in utero, her grandparents had moved from a farm near Beardsley, Minnesota, into a house on Edgerton Street, just two blocks away from their soon-to-be granddaughter.

Some of Margaret’s most lasting childhood memories were of her grandfather. Ed had a job as nightwatchman for the Twin City Rapid Transit Company, which operated the streetcar system in Minneapolis and St. Paul. As an employee, he could ride for free. On his days off, he would ride around town visiting friends and chatting up the waitresses at his favorite restaurant on the corner of University and Snelling. When Margaret was nine or ten, she regularly accompanied him on his social rounds. She got to explore the city and meet all sorts of people. Her grandfather would jokingly introduce her as his “chaperone.”

Minnesota Historical Society, http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10732818.

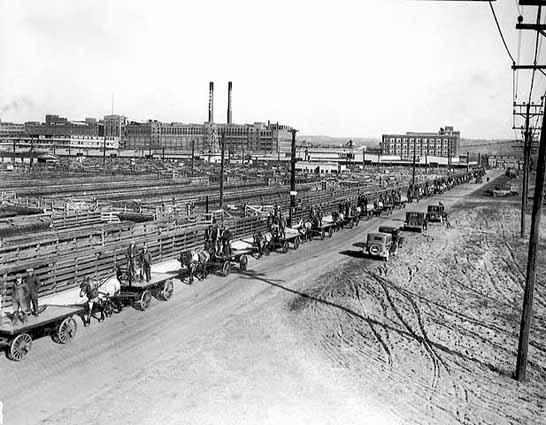

Another distinctive memory Margaret had from around the same age was of clandestine meetings at her house. For sixteen years, from 1928 to 1943, her father Basil worked at the enormous St. Paul Union Stockyards in South St. Paul. During most of his tenure he was a teamster. Early in the Great Depression, he struggled to get enough hours, often working only half days, and Margaret’s mother Isabelle got a job at a local restaurant to help make ends meet. By 1937, Basil had the opposite problem, routinely putting in 60 to 70 hours a week—without overtime pay. (Basil’s compensation record and the rest of his personnel file are archived at the Minnesota Historical Society.)

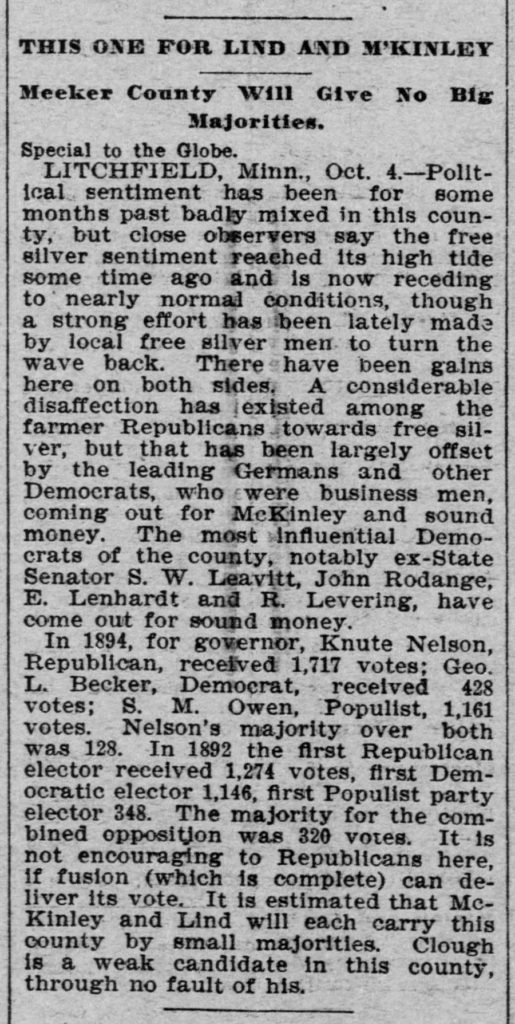

The secret gatherings Margaret remembered her father hosting were organizing meetings for the union. Basil’s union activities were part of the broader Twin Cities labor movement of the ’30s. Based on the Minnesota Historical Society’s photograph collection, strikes at the stockyards took place in 1932, 1933, and 1938. Basil may also have taken part in the Teamsters strike of 1934, which was centered in Minneapolis. Margaret and Patrick knew about their father’s meetings but were sworn to secrecy.

Minnesota Historical Society, http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10669809.

Minnesota Historical Society, http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10729180.

On November 11, 1940, Margaret was 15 and a freshman at Johnson High. It was a warm morning, so she wore only a skirt and blouse when she left her family’s house on Payne Avenue for her one-mile walk to school. But by the time she had to make the long walk home, a blizzard was raging. She recalled wrapping newspapers around her legs in a futile effort to keep warm. Like many other Minnesotans that day, Margaret survived the Armistice Day Blizzard—but barely. This experience too stuck with her for the rest of her life.

Minnesota Historical Society, http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10750540.

At school, Margaret was a very active student. She took part in Spanish club, bowling club, archery, and was on the Board of the Girls Athletic Association. She was part of a traveling folk dancing group and was also a talented speed skater. Margaret was especially proud of the school letter she earned for athletics at a time when most girls were discouraged from participating in sports.

Margaret graduated from Johnson High in 1943. This was in the middle of World War II. Many of her male classmates went off to basic training and then to Europe or the Pacific. Margaret started working as a Rosie the Riveter. Every day she travelled to Holman Field, an airfield across the Mississippi River from downtown St. Paul. She and several thousand other workers—mostly women—retrofitted B-24 Liberator and B-17 Flying Fortress bombers with high-altitude oxygen and ventilation systems and new, top-secret H2X radar systems.

Northwest Airlines via NWA History Center

In the fall of 1943, Margaret’s father Basil quit his job at the stockyards. He, Isabelle, and Patrick moved to Durand, Wisconsin. Since Margaret had a high-paying job at Holman Field, she stayed in St. Paul. She moved in with the family of her aunt Bessie at 331 Geranium Ave. Bessie’s husband Martin Aasen was a butcher at a Swift & Co. packing plant in the same South St. Paul stockyards complex.

Margaret’s grandfather Edward Daly had died in 1937, but her grandmother Jane Daly now lived with Bessie, Martin, and their 11-year-old son—Margaret’s cousin—Dick. Jane had early-onset dementia, and Margaret helped Bessie care for her until her death in 1945.

When the war ended in 1945, all the men came back from overseas. For the rest of her life, Margaret bitterly resented being forced out of a good-paying job and into the role of homemaker. But that’s what she did, and she did it well.

A Wife and a Mother

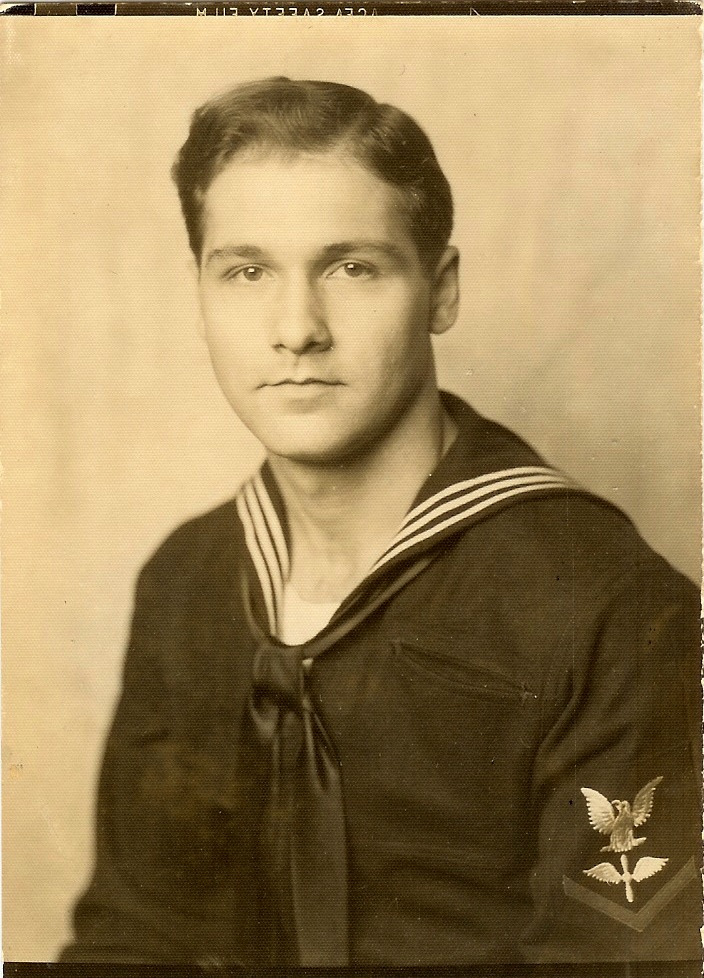

Two of Margaret’s good friends from school were Dorothy LaBelle and Dorothy’s first cousin Marge LaBelle. Margaret had met Dorothy’s older brother Gerald back in her school days. She started seeing him after he returned the Pacific. Margaret and Gerald wed on June 20, 1946, at St. Patrick’s Catholic Church in St. Paul—their home church.

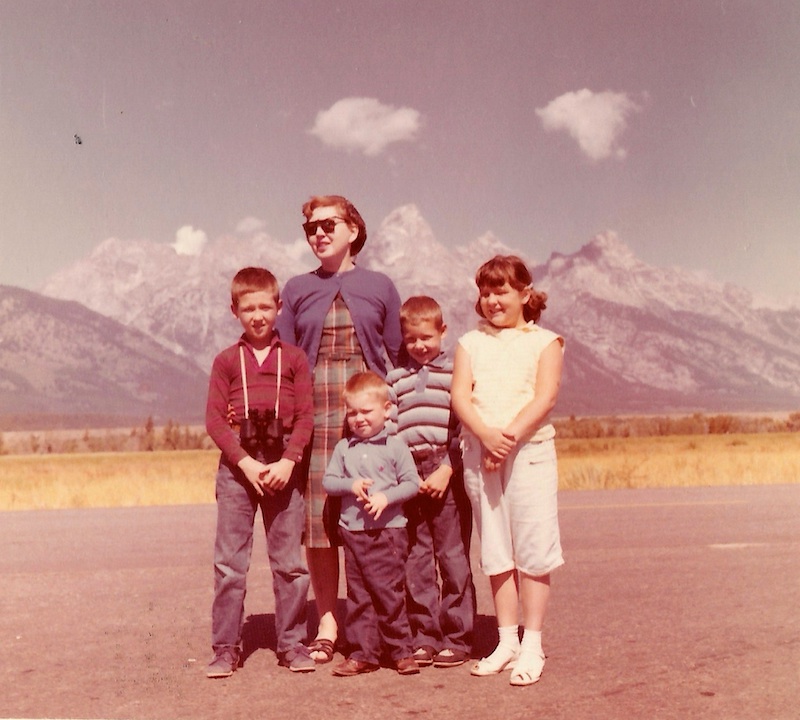

Five children followed between 1947 and 1958: Gerald, Jr.; Greg; Maureen; Mark; and Ross. Their early years of parenthood were a challenge. Little Jerry, Jr., was born with cerebral palsy after a difficult childbirth. Then, as a small boy, he contracted polio. In 1951, Margaret and Gerald made the difficult decision to appoint a state guardian for Jerry. He lived the rest of his life in state hospitals or group homes before his death in 2005. (This was many years before in-home care for someone with significant disabilities was an option like it is today.)

In 1953—after a very brief residence in Belvidere, Illinois—Margaret and Gerald bought a house at 388 Geranium Avenue East in St. Paul, less than a block from the home of Margaret’s aunt Bessie. Margaret would reside in that house for the next 62 years.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Margaret was a busy mother and an active member of St. Patrick’s Church. As a mother, she did all kinds of creative arts with her kids. She made doll cakes, fancy sugar eggs for Easter, and marzipan candies in the shapes of fruits and vegetables. She was a cub scout den mother. At church, she helped organize and run the fall festival and spaghetti dinners, and she served as one of the “church basement ladies,” cooking countless meals for church functions. If that wasn’t enough to keep her busy, she also occasionally worked as a department store clerk. And she was a regular hostess. Her extended family—especially her many paternal cousins—were regular guests in her home.

On Her Own

Then, in 1969, Gerald abruptly left the family. The ensuing divorce and annulment left lasting scars on everyone in the family, but especially on Margaret. In fact, the divorce went all the way to the Minnesota Supreme Court, where it helped establish case law that is still studied by prospective lawyers today.

In a few short years, Margaret effectively lost her whole family. Her mother Isabelle had died of ovarian cancer in 1967. Her husband abandoned her in 1969. One by one, her children left for the Air Force or college or to live on their own. And now she had to support herself.

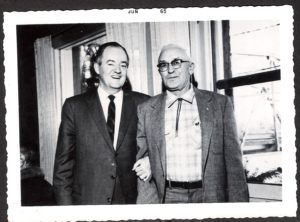

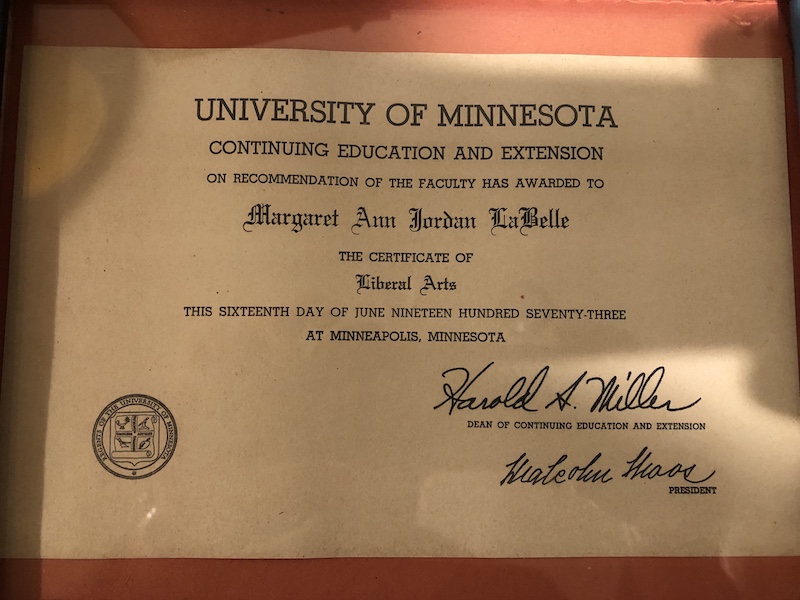

In June 1973, Margaret earned a two-year Certificate of Liberal Arts from the University of Minnesota. At age 48, this was one of her proudest accomplishments. She had also recently begun a new job at West Publishing Company. Margaret supported the company’s traveling salesmen, making sure they had everything they needed while on the road and arranging supply shipments as needed. It wasn’t the professional career she had envisioned for herself in 1945, but it paid the bills. And she made several good friends there. Margaret stayed at West Publishing until she retired in June 1990.

Besides working, Margaret rededicated herself in her Catholic faith. She continued to volunteer at church, and she became a member of the Legion of Mary, an association of Catholics dedicated to spiritual and social welfare through prayer and apostolic works.

After she retired, Margaret went on numerous pilgrimages to important Catholic sites in North and South America, often with her friend Ceile Swenson. They visited sites up and down the U.S. East Coast and in South Bend, Indiana. In 1994, they visited Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City and a year later traveled to the Shrine of Betania in Cúa, Venezuela, the location of thousands of apparitions of the Virgin Mary and a Miracle of the Eucharist Host. Then in 2000, they traveled to Birmingham, Alabama, to join the studio audience as Mother Angelica filmed an episode of her famous TV show, which was broadcast on the Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN). While in Alabama, Margaret and Ceile also stopped at Our Lady of the Angels Monastery and the newly built Shrine of the Most Blessed Sacrament, both of which—like the EWTN network—had been established by Mother Angelica.

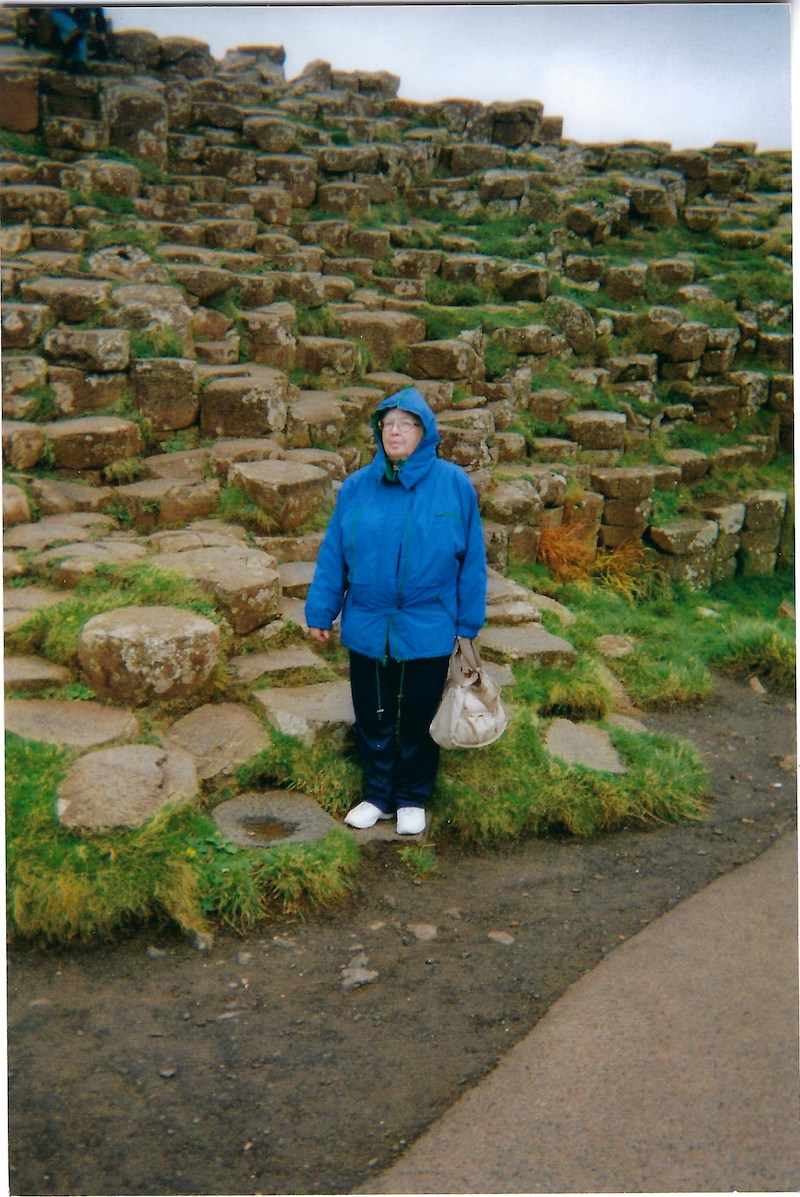

A few years later, Margaret took a different kind of trip. In 2004, when Margaret was 79, she had the pleasure to visit Ireland with her cousins Colleen and Cindy. Margaret was enormously proud of her Irish heritage—every branch of her family tree traced back to the Emerald Isle—so this was the trip of a lifetime for her.

Inevitably, age eventually caught up to Margaret. In 2015, after 62 years in her house on Geranium Avenue and 90 years(!) as a member of St. Patrick’s church, Margaret moved into Cherrywood Pointe of Forest Lake. She lived independently until age 92, and then in assisted living until her death.

When she was in her 90s, her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren enjoyed celebrating each birthday with her (except for her 95th, which was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic). Her family brought brunch, played games, and kept counting higher every year!

She was a tough woman to the end. She survived a heart attack at age 85—followed by a triple bypass and surgery to clear her carotid arteries—a stroke at 86, and numerous serious illnesses in her 90s, including influenza. Even in her last week of life, she told visitors she planned to get better. The hardest part of her final years was the dementia which took hold after her stroke. But while her short-term memory failed, she could still remember details about being a child and young adult. During one visit in October 2019, I recorded her talking about her experiences in the 1930s and 1940s. That discussion informed some of this story.

Margaret Anne LaBelle died peacefully in her sleep, March 9, 2021, at Cherrywood Pointe of Forest Lake, following two months under the compassionate care of Ecumen Hospice.

A Difficult Life, But a Life Well Lived

A simple narrative like this can never capture the full picture of a person’s life. Margaret had a wide range of hobbies and interests. A true Minnesotan, she liked to fish. She loved reading, especially biographies and histories. From an early age, she had a fondness for painting, sewing, and gardening. She loved clothing and jewelry and collected all sorts of outfits over the years.

Margaret was generous—almost to a fault. She supported dozens if not hundreds of charitable causes in her life (perhaps including a few fraudulent ones). At Thanksgiving, she would gladly invite anyone in the neighborhood who had no place else to go. Even late in life—when she was well into her 80s—Margaret offered a room in her house to someone in need.

She was predeceased by her parents, brother Pat, and son Jerry, Jr. She is survived by her children Greg (Johnny), Maureen (Wes) Vanek, Mark (Jenny), Ross (Joni); grandchildren Erik (Jennifer) LaBelle, Carrie (Tim) Hill, John (Pam) Vanek; and great-grandchildren Ally, Cece, Lucy, and JJ LaBelle, Carson and Caleb Hill, and Eliza and Lena Vanek, as well as other family and friends.

Margaret was buried Friday, March 12, 2021, in Resurrection Cemetery in Mendota Heights, next to her son Jerry LaBelle, Jr. Paul bearers were Ross LaBelle, Wes Vanek, John Vanek, Carrie Hill, Erik LaBelle, and Ally LaBelle. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, only Margaret’s immediate family attended the funeral. Margaret went out as she came in, a proud Irish Catholic. Father Tom Fitzgerald led her funeral service. And, at Margaret’s request, the service was full of Irish music: “Danny Boy,” Carrickfergus,” “Into the Mystic,” the ancient Irish hymn “Be Thou My Vision,” and the jig “The Irish Washerwoman,” among others.