Here in the Upper Midwest, the weather is about to turn frigid. It’s four degrees Fahrenheit as I write this and forecast to hover around zero all week. It happens every year, but it’s still a notable event when the Arctic air finally arrives. The bitter cold forces everyone to change behavior. More time reading under a blanket or sitting by the fireplace, less time outside. It takes longer to go anywhere for the simple fact that one needs to put on so many layers of clothing before stepping into subzero temperatures. (You know this to be especially true if you have young children.)

With the onset of frigid weather, I thought I would write a short post about my 4x-great-grandfather František “Frank” Filipi, who had a dreadful relationship with winter. Indeed, it killed him. The story of Frank’s suffering and ultimately his death at the hands of Old Man Winter is the fourth installment in the GeneaLOGIC blog series “You Died How?”.

Meet Frank (again)

We’ve already met Frank. He was a minor character—in the role of father-in-law—in the story of my great-great-great-grandfather Jacob Kobes, who died in his own winter accident in 1895. In that story, we learned that Frank Filipi’s family lived in Racine County, Wisconsin in the 1860s and moved with the Kobeses to Saline County, Nebraska, in 1869 to acquire land under the 1862 Homestead Act.

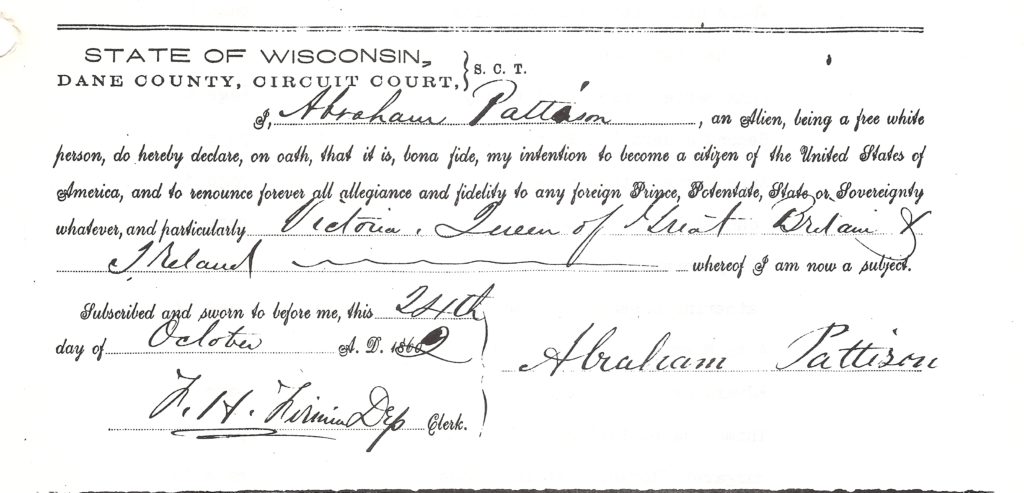

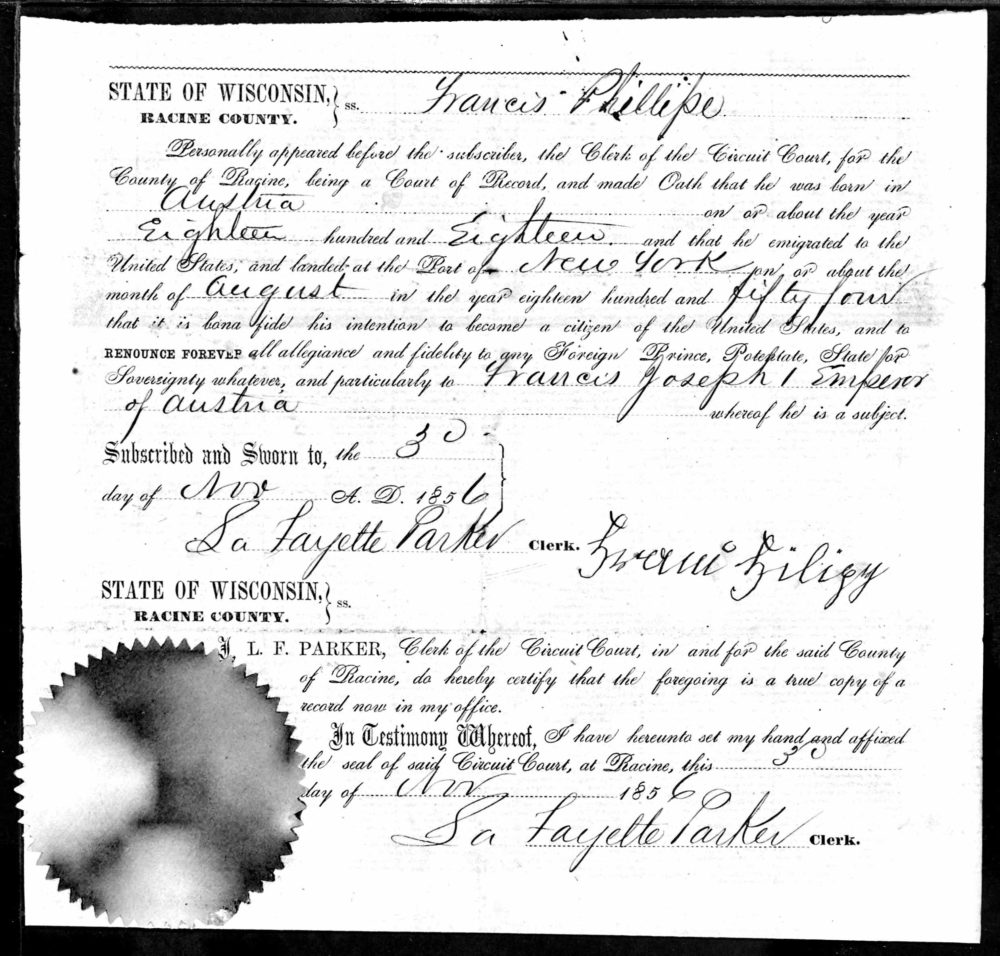

Frank was born in about 1821, possibly in the village of Ceská Trebová in eastern Bohemia. Records about him are scarce. He declared his intention to become a U.S. citizen in 1856 in Racine County, Wisconsin, and then claimed land in Nebraska in 1869. Aside from Homestead records (which include copies of some of his immigration documents), the Filipi family has been almost impossible to track down. The family is missing from both the 1860 and 1870 censuses. I honestly believe Frank may have been trying to conceal his identity whenever he could. Perhaps he was still paranoid about reprisals from his possible involvement in one of the failed revolutions in Europe in 1848. I plan to write a separate blog post about all the missing and misleading records about Frank and his family.

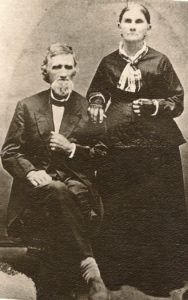

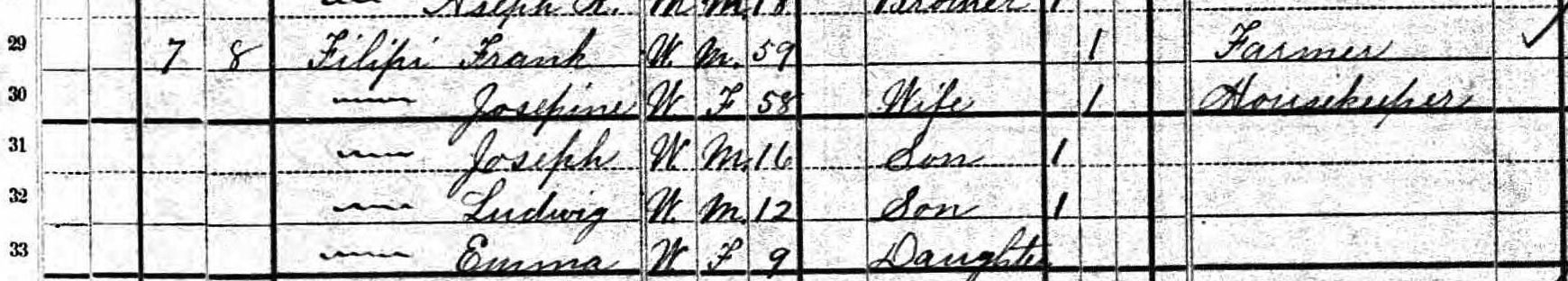

Only one census record definitively shows Frank and his family. In 1880, we find Frank and his wife Josephine in Wilber Precinct (as townships are called in some Nebraska counties), Saline County, Nebraska, one household away from the family of their daughter Marie Filipi Kobes and her husband Jacob. Frank and Josephine Filipi were both approaching sixty years old (though other records suggest Josephine was a bit younger than that). Three children still lived at home with them: 16-year-old Joseph, 12-year-old Ludwig, and 9-year-old Emma.

The agricultural schedule tells us that Frank owned 80 acres of land, with 60 acres under till. The variety of crops the Filipis grew was mostly unexceptional: wheat, corn, oats, rye, and potatoes. The Filipis stood out somewhat from their neighbors in that they had produced in 1879 not just milk, like all the other farmers, but 25 lbs. of cheese. They also harvested a small grove of peach trees.

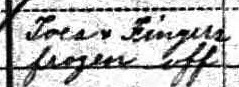

The most notable thing about Frank, however, comes from the population schedule. Column 15, under the heading Health, asked, “Is the person . . . sick or temporarily disabled, as to be unable to attend to ordinary business or duties? If so, what is the sickness or disability?” Next to Frank Filipi’s name, the census enumerator wrote “Toes & Fingers frozen off.”

Well that’s gruesome. One can imagine a dozen scenarios in which a farmer in Wisconsin or Nebraska might have succumbed to frostbite. Had he been caught in a surprise blizzard and been unable to find his way back to the house? Or had he merely been careless while traveling one winter day, failing to realize the damage the cold was inflicting upon his body until too late? As with many genealogical questions, we may never know. We can speculate that Frank’s lack of toes may have played a role in his even more gruesome death a few years later.

A Gruesome End

March 1886 was cold and snowy throughout Nebraska. The weather summary for March printed in the Annual Report of the State Board of Agriculture, reads, “The most striking feature of the month of March has been the unprecedented snow fall of 25.3 inches, the normal amount for March being 4.6 inches. . . . The precipitation, the number of days of precipitation, and the proportion of cloudy days have been correspondingly large.” Likewise, “The temperature has been about five degrees below normal, being the coldest March, except that of 1881, for the past nine years.”

The total of 25.3 inches was an average of observations made across the state, but mostly in southeastern Nebraska, where Frank lived. In fact, we can make an educated guess at how much snow fell in Wilber. Both Crete, eleven miles north of Wilber, and De Witt, seven miles south, had weather stations. Crete recorded 2.39 inches of precipitation that month, while De Witt reported 1.8 inches. Assuming most of that precipitation fell as snow and using a ratio of about 8:1 (typical of wet spring snow), we can calculate that Wilber saw between 15 and 20 inches of snow in March 1886.

Into this world of snowdrifts, daytime thaws, and nighttime freezes, walked Frank Filipi and his missing toes. It was the middle of the month, still a couple weeks before the weather finally warmed up for good. Perhaps it was Sunday, March 14, and Frank and family were strolling through Wilber with their fellow churchgoers. Maybe it was Tuesday the 16th, as Frank made a quick run into town for supplies of some sort. For whatever reason, Frank was walking the business blocks in the village of Wilber on foot. All it took was on misstep. He slipped on a patch of ice, flew into the air in a classic winter pose, fell into the opening of a basement entry to one of the businesses, and broke his neck.

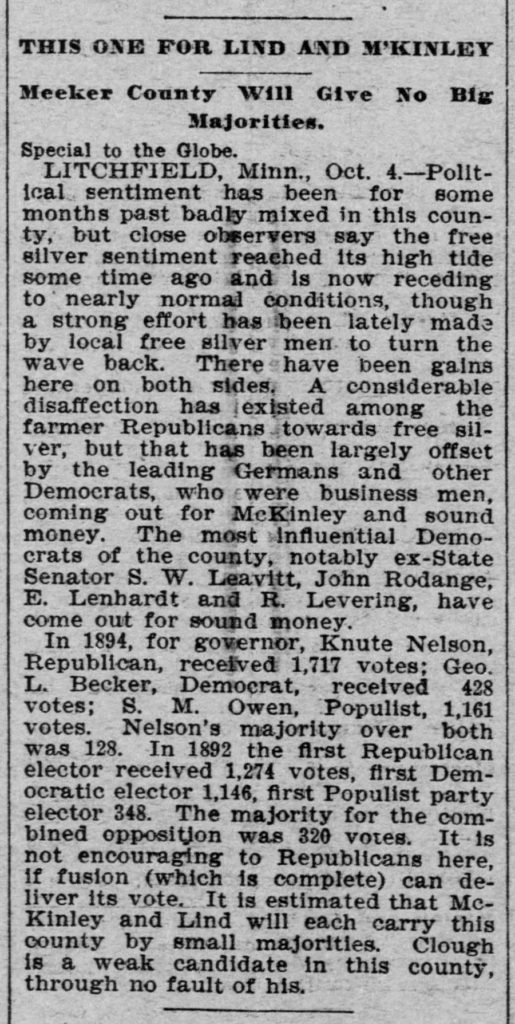

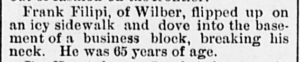

The only report I’ve found of his death was a succinct summary printed in the Omaha Daily Bee on Wednesday, March 17 (above), which is short on both details and empathy. No doubt Frank’s family missed him and were shocked by his sudden death. If there is a silver lining, it’s that Frank was already 65 years old. He hadn’t been all that much use around the farm since he lost his fingers or toes. Recall that his disability was recorded under the heading “unable to attend to ordinary business or duties.” All his children were grown. By 1886, Frank was far more dependent on other people than anyone was on him.

Let Frank’s tragic death serve as a reminder to all of us in advance of the cold and snow. Be careful out there. And if you see someone having trouble getting around on an icy day this winter, give them a hand. If snow and ice are treacherous for you, they’re even more annoying and dangerous for people in wheelchairs, visually impaired people with white canes, and others, like Frank, whose lack of toes was probably not evident but whose lack of balance might have been.